Over on Twitter, there’s been an interesting debate raging about the role of the GRE. The GRE, or Graduate Record of Examination, is a standardized test of verbal and quantitative ability that is frequently used by admissions committees selecting students for research degrees.

A number of schools are rethinking their use of this test (as you can read about by following the #GRExit hashtag on Twitter), and a heady debate has followed about whether these moves are equity-enhancing or equity-deteriorating.

What this conversation has raised, for me, is how poor a job many institutions do at removing bias and racism from the other parts of their admissions procedures. The employee recruitment and selection literatures tell us a great deal about how to do a better, less biased, and more inclusive job at hiring. My impression is that many admissions processes ignore these insights entirely.

If we are going to rely less on the GRE and other standardized tests, we need to do a much better job of debiasing the other ways we measure aptitude, potential and fit in grad admissions. My initial response, half joking, was that admissions committees without the GRE could just fall back on the gold standard of bias-free decision-making: The reference letters from profs! But, of course, after the jokes, the real question is: What changes to grad admissions norms would improve access, reduce the structural racism of the process, reduce bias in selection, etc.?

Here are four ideas. They’re all reasonably easy to do for committees (though for some of them, there’s work involved). More importantly, though, I don’t think most of them require major institutional policy changes. They’re things that members of an admissions committee could likely do on their own within existing procedural frameworks.

Let’s take the “secret code” out of statements of interest. For many undergraduates, their only experience with crafting a statement (if they have any experience at all with it) is probably with the undergraduate personal statement. So, many of us have probably seen statements of interest that start with stories about the student’s formative and childhood experiences and their ambitions in life, et cetera. And these aren’t what we’re looking for. What we’re seeking from these statements is basically a demonstration that the student knows how to ask a good research question, has a good fit with faculty member interests, and has a set of career goals that is consistent with the program. But at most schools, we don’t give a template. We don’t give examples. We don’t give a checklist of items to cover. So, when we read these statements, we’re often just capturing whether students know the “inside baseball” of what committees are hoping to see. And where do they learn this? By having elite social networks: Friends and families in grad school or academic careers, faculty mentors, et cetera. So, let’s take out the mystery: Make it clear what needs to be in these statements, and how the statements are used in making decisions.

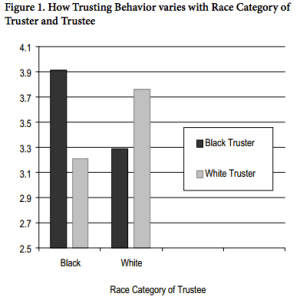

Let’s do away with unstructured interviews. The apprenticeship and lab models of grad training often prioritizes the student-supervisor dyad as the most important fit. So, it’s natural that our first connections with prospective students are often done through casual one-on-one phone or video calls. It’s through those initial informal chats that we make decisions about whether a student is the right fit or match. And we make overall judgments based on our instinct and our accumulated experience. But let’s recognize this for what it is: It’s an unstructured interview. And we know that unstructured interviews are both poor predictors of performance, and tend to reward social and demographic similarity. And, our global, overall appraisals put more value than we might want on people’s culturally-specific social skills and verbal fluency. And, whether we want to admit it or not, unstructured interviews are a “beer test”: “Would I want to go out for beers with this person?” If we want to improve access and representation, we need to stop choosing students on their similarity to ourselves. The fix is easy: Use structured interviews. Have more than one interviewer. Choose your questions carefully, and ask all your applicants the same questions. Have each interviewer rate each applicant independently without conferring first. Use standardized rating scales that are anchored to specific behaviours you’re looking for. This won’t feel natural, but the research is clear: It’s how you stop selecting on social and demographic similiarity in interviewing.

Let’s think about adding work samples to selection processes. Many of us love undergraduate applicants with experience doing an undergraduate thesis, because it shows that they have experience and aptitude for the kind of independent research work they’ll be doing in grad school. But, of course, the chance to do hands-on independent research is much easier in some institutions than others. So, if we select on undergrad research experience, we’re selecting to some degree on elite institutions. So, let’s do what many employers do, and create opportunities in the selection process for work samples. What this might look like will vary, but here’s an example: Give students a simple, accessible introduction to a topic, and then have them identify research questions, develop or refine a research design, or do something else that helps you see their aptitude for ‘thinking like a researcher’. And, debias this process. As you would with interviews, make sure you have a consistent task, clearly defined criteria, and multiple independent raters. You may even have blind ratings, rating applicants’ work samples without their names or other identifiers.

Lastly, let’s reform how we ask for and use reference letters. This whole post started with a joking tweet about the uselessness of reference letters. And in their current state, they are: They’re a status-signalling device, and reward people with the cultural capital and institutional opportunities to build close relationships with tenured or TT faculty members with ‘name recognition’. The content of the letters may themselves reflect cultural idiosyncrasies. The rating scales (top 5%, 10%, 25%, etc.) can also be hard to interpret, because ratings may either be lenient (trying to write a “good letter” by giving a top-5% rating), or institution-specific (“hey, top 25% in a highly selective school is a great rating!”). A better approach is to request evaluations with rating scales that are anchored to specific categories of behaviours or frequencies of behaviours–and to think carefully about picking behaviours that actually matter to success in the program, rather than measures that reflect cultural styles or other less relevant criteria.

None of this should be seen as surprising or innovative. Any of us who teach any basics of selection in our classes will recognize these characteristics from any introductory HRM, OB, or I/O psych textbook. They’re not state-of-the-art science. They’re just basic, nuts-and-bolts, evidence-based approaches to effective and bias-free selection. But there are a lot of schools (even in places who study selection, discrimination, and related topics) that still use selection techniques and instruments that make the GRE look positively benign by comparison. So, if your school is dropping the GRE for equity and access reasons, or just dropping it because of COVID complications, now would be a great time to take a critical look at the rest of your selection process.